Share this article and save a life!

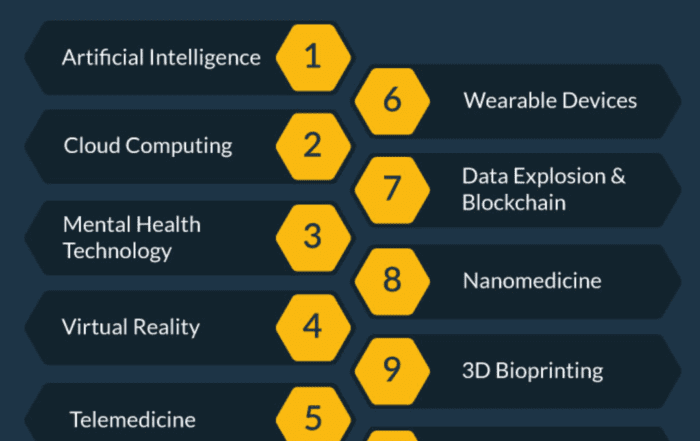

Physicians and clinicians have used clinical decision support (CDS) software for decades to inform decision-making. Current tools that use artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms and machine learning (ML) models generate impressive recommendations and predictions. Are physicians at risk of becoming over-reliant on these tools?

That concern is one reason the FDA issued guidance—now final—around regulating CDS software. Issued in September 2022, the final guidance outlines which types of CDS it considers medical devices—and therefore subject to FDA regulation—and which types are not.

The Varied CDS Landscape

CDS encompasses a wide range of tools, from EHR integrations to predictive AI-enabled software. When powered by AI/ML, CDS systems can analyze large datasets to derive insights in a way not possible by humans.

On one end of the CDS spectrum, you have simple information checkers built with if/then rules. Software that checks for drug-drug interactions and medication duplication is one example. When it finds a match, it issues an alert. The doctor takes note and adjusts the prescription as needed.

Compare that with advanced AI-enabled CDS software. Systems like Viz.ai and Rapid.AI analyze CT and MRI scans for signs of stroke, aneurysm, and cardiovascular disease. They go beyond alerts to identify and characterize suspected diseases with remarkable accuracy. These tools also make radiological images available on physicians’ mobile devices in real-time, which helps speed up triage and treatment. During a life-threatening emergency, a few minutes can make a dramatic difference in that patient’s outcome.

The Revised FDA Framework

The FDA’s final guidance aims to clarify the scope of the FDA’s oversight over CDS in all its guises. In doing so the FDA changed the criteria of what products must be regulated as medical devices. The reaction to the document has been (to put it politely) mixed.

The guidance took many medical device companies and regulatory experts off guard for a few reasons:

- It was a substantial departure from the 2017 and 2019 draft guidances. Some called it a total rewrite.

- It made clear that the FDA intends to increase its regulation of CDS tools. Products previously not regulated are now potentially subject to FDA oversight.

- Instead of implementing risk levels, as stated in the 2019 guidance document, the final guidance relies (and elaborates) on four criteria from four criteria in section 520(o)(1)(E) of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act). The extra text includes a discussion on automation bias.

It’s Not Over Yet

The goal of the FDA, with any type of drug or device, is to protect patients by ensuring products are safe and effective for their intended use. But with more oversight over even low-risk products, developers argue the guidance creates unnecessary regulatory hurdles and stifles innovation.

For these reasons and others, the Clinical Decision Support Coalition, a group of CDS stakeholders that formed in 2012, is pushing back against the final guidance. In early February, the coalition filed a Citizens Petition to request that the FDA rescind its final guidance.

In essence, the coalition asserts the FDA crosses the line between regulating medical devices and regulating the clinical practice. They also state the final guidance violates the 21st Century Cures Act, which sets limits on FDA’s authority to regulate certain CDS software functionality.

Part of the problem is the guidance’s definition of “medical information” for purposes of regulated CDS software. The coalition’s petition says the FDA’s definition is too narrow and would require “all such information to meet certain quality standards associated with peer review, in violation of the Cures Act.”

In a podcast, Bradley Merrill Thomson, a lawyer and chief data scientist at Epstein Becker Green who focuses his practice on FDA, FTC & AI regulation, said the Cures Act exempts from FDA regulation

“any analysis done of data, without limitation to quality, and presented in any form of recommendation, whether a singular recommendation or a list of possibilities.” Most machine learning models rely on real-world data. “By imposing quality requirements, the FDA put a major obstacle in the way of anyone who wants to use machine learning,” Thompson said.

Are Physicians at Risk of Autopilot?

The final guidance also discusses the risk of automation bias. It defines automation bias this way:

…the propensity of humans to over-rely on a suggestion from an automated system. In the context of CDS, automation bias can result in errors of commission (following incorrect advice) or omission (failing to act because of not being prompted to do so). Automation bias may be more likely to occur if the software provides a user with a single, specific, selected output or solution rather than a list of options or complete information for the user to consider. In the former case, the user is more likely to accept a single output as correct without taking into account other available information to inform their decision-making.

In time-critical situations, the risk of automation bias increases, the FDA argues, because there isn’t enough time for the user (presumably a physician or clinician) to consider other information (presumably what they’ve learned from years of studying and practicing medicine). The FDA used research from aviation e.g., auto-pilot, to inform its theory.

Products that pose a legitimate risk of automation bias would be regulated by the FDA under the final guidance. It makes sense. A device that provides information specific and detailed enough that would potentially prompt over-reliance by physicians may need to be regulated as a medical device. These products also need to be backed by substantial published clinical evidence.

Then again, is the industry assuming physicians as complacent? A literature review that analyzed data across industries found automation bias to be subjective. A user’s cognitive style, trust in technology, and workload, among other factors all play a role in automation bias. The review also identified several guardrails developers can put in place to limit the risk of automation bias.

Ty Vachon M.D. the Co-Founder and CEO of Oatmeal Health states it perfectly,

Essentially every decision we as humans make, conscious or unconscious, is subject to multiple biases. This includes clinical decisions with and without outside support. In the ideal setting, clinical training prepares providers to be aware of and account for biases. The best clinical decision support systems will go one step further and expect biases in all forms and provide meaningful feedback mechanisms to not only guide decision making in the short term but the long term as well. Specifically, the system should be designed to track outcomes, and if automation bias is suspected, adjustments should follow to properly guide providers.

The concept of automation bias isn’t new, and its mention isn’t new for FDA CDS guidance. Sonja Fulmer, assistant director for digital health policy for the FDA’s Digital Health Center of Excellence (DHCoE), said at the December 2022 Food and Drug Law Institute (FDLI) digital health conference that the concept of automation bias and risk was mentioned in previous guidance, but it wasn’t explicit, referred to briefly under the IMDRF framework. The final guidance addresses the issue directly.

What Does This Mean for Healthcare Providers?

Companies developing CDS software, and physicians advising on said software, should take a close look at the guidance document. From there, consult your lawyer with any concerns.

The best practices below don’t replace that phone call to a regulatory advisor. Consider these bullet points as research-based clues to point you where you need to go.

- If you’re involved in developing CDS software: to determine if a CDS function falls inside or outside the scope of a medical device, consult with the FDA to define a path forward. Follow the advice I’ve heard agency reps give multiple times: engage early and often.

- If you’re evaluating CDS software for your healthcare practice: look for “explainability.” Look for labeling that explains how the software works and how it arrives at its conclusions. Under the final guidance, devices that do not need to be regulated as the medical device must include this type of labeling. However, the final guidance is notably vague on this subject. If it’s impossible to know or explain how the algorithm worked its magic, it’s probably regulated.

- If you’re evaluating regulated AI-enabled CDS software for your practice: review the studies evaluating its sensitivity and specificity. Look for multiple published studies using large diverse datasets to test and validate the device.

The Silver Lining

Multiple federal agencies, including the FDA, have been rooting for more innovation, not less. And MedTech innovators will continue to develop, test, and release products that ultimately help improve patient outcomes.

As it stands, the final guidance raises a lot of questions that will hopefully get ironed out in the months to come. If left as is, following the guidance could make innovation more complicated, but it sure won’t stop. Ultimately, that innovation—regulated or not—will help healthcare providers do their jobs more efficiently while delivering even better care to the patients they serve.

Heather R. Johnson leads OutWord Bound Communications, a content marketing consultancy, and word shop for MedTech, life sciences, and healthcare technology companies. OWB helps organizations of all sizes evaluate, plan, and execute content strategies that hit the mark.

Share this article and save a life!

Author:

Greetings. I’m Heather Johnson. I launched OutWord Bound Communications in 1999. I help B2B companies—primarily in drug development, medical device/MedTech, and healthcare technology—plan and develop technical and/or scientific content. I provide quality content that builds brand awareness and trust, engages and educates your audience, and helps convert interested prospects into loyal customers.