Share this article and save a life!

African American/Black individuals have a disproportionate cancer burden, including the highest mortality and the lowest survival of any racial/ethnic group for most cancers. Every 3 years, the American Cancer Society estimates the number of new cancer cases and deaths for Black people in the United States and compiles the most recent data on cancer incidence (herein through 2018), mortality (through 2019), survival, screening, and risk factors using population-based data from the National Cancer Institute and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2022, there will be approximately 224,080 new cancer cases and 73,680 cancer deaths among Black people in the United States. During the most recent 5-year period, Black men had a 6% higher incidence rate but 19% higher mortality than White men overall, including an approximately 2-fold higher risk of death from myeloma, stomach cancer, and prostate cancer.

A report by Deloitte concluded that health inequities account for approximately $320 billion in annual healthcare spending signaling an unsustainable crisis for the industry. If unaddressed, this figure could grow to US$1 trillion or more by 2040.

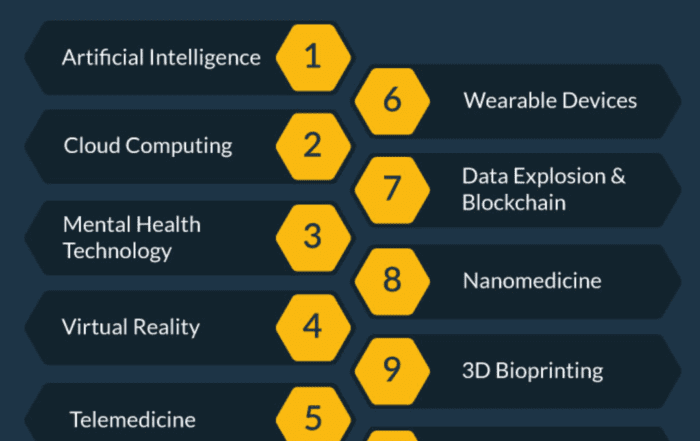

These disparities are unacceptable and must be addressed as a national priority. There are several factors that contribute to these disparities, including socioeconomic status, lack of access to healthcare, and cultural barriers. Additionally, there is a lack of diversity in the healthcare workforce, which can also contribute to these disparities.

Overall Cancer Occurrence

In 2022, an estimated 111,990 Black men and 112,090 Black women will be newly diagnosed with invasive cancer. The most commonly diagnosed cancers among Black men are prostate (37%), lung, and bronchus (hereinafter lung) (12%), and colon and rectum (hereinafter colorectum) (9%).

Disparities in Health Outcomes

One of the most striking examples of health inequities in America is the disparities in life expectancy between different populations. According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the overall life expectancy in the United States is 76.1 years. However, this number varies significantly depending on factors such as race, socioeconomic status, and geography.

For example, the life expectancy for the average black person in the United States is just 70.8 years, 6 years less than the overall average, and even less for black men (66.7 years). Similarly, the life expectancy for the average Hispanic person in the United States is 77.7 years, while the life expectancy for the average white person is 76.4 years.

Another area where health inequities are evident is in infant mortality rates. The United States has one of the highest infant mortality rates among developed countries, and this rate is significantly higher for certain populations. For example, the infant mortality rate for black infants is more than twice as high as the rate for white infants.

Disparities in Access to Healthcare

Access to healthcare is another major contributor to health inequities in America. Despite the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), also known as Obamacare, many Americans still lack access to affordable and high-quality healthcare. This is particularly true for low-income individuals and communities of color.

According to data from the Kaiser Family Foundation, nearly one in four non-elderly adults with incomes below the poverty level were uninsured in 2019. This is compared to just 6% of non-elderly adults with incomes above 400% of the poverty level. Additionally, Hispanic and black individuals are more likely to be uninsured than white individuals.

Even for those who do have insurance, access to healthcare can still be limited. This is especially true for individuals living in rural areas, where there may be a shortage of healthcare providers. Additionally, individuals living in low-income communities may have limited access to transportation, making it difficult for them to get to medical appointments.

Mistrust in our Government and Health Systems

This one hits home for me, and even more so in the last few years with the complete destruction of our government and the lies and deceit that is all too prevalent. Our goals as a nation and its people are misaligned with the goals of individuals in Congress and the Senate and we can no longer allow these groups to control the destinies of Americans struggling just to eat and pay rent.

Trust in health care has been eroding for decades in the United States. Between the mid-1960s and the 2010s, the percentage of American adults who reported having confidence in healthcare leaders declined from 73 percent to 34 percent. Especially among marginalized patient populations, including BIPOC, discrimination and malfeasance in medical care and research (as described earlier in this paper) have created a legacy of distrust. One in five U.S. adults reports experiencing discrimination in the health care system, with racial and ethnic discrimination the most reported form [68]. For vulnerable and marginalized communities, distrust of the healthcare system can be seen as a wise and necessary mechanism for identifying threats and creating change.

However, a lack of trust in health care professionals and the health care system is also associated with the underutilization of health services and disparities in health outcomes. When asked, healthcare professionals both recognize this lack of trust and understand that it is a significant barrier to equitable care.

Valuable resources like the AAMC’s “Principles of Trustworthiness Toolkit” can empower leaders, clinicians, teams, and patient-facing staff to create more trusting relationships with patients and their families, and communities. But, a host of resources can be overwhelming and lack strategic focus. Having guidance, concrete approaches, and expert support to prioritize and implement a trust-building plan maximizes impact and growth for the investment of time and money.

The Impact of Racism and Discrimination

Health care in the United States has a long history of institutionalized and interpersonal racism and discrimination that continues to impact BIPOC today.

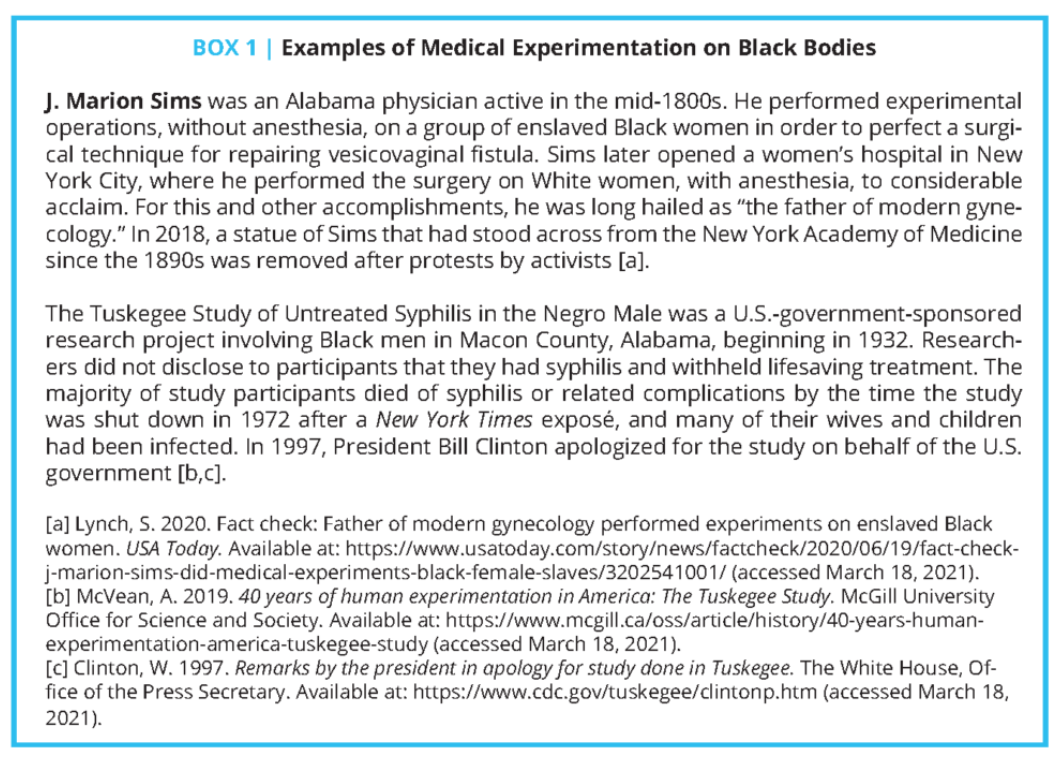

Some of the starkest examples of how care delivery has exemplified many forms of systemic racism include reprehensible experimentation on Black bodies from the era of slavery – as demonstrated by the work of physicians such as J. Marion Sims – through the Jim Crow period, such as the Tuskegee Study (see Box 1). Since then, access to high-quality care has continued to be limited for BIPOC, as noted later in this section. Even elements of the social safety net have been chronically under-resourced and yielded inequitable outcomes for racial and ethnic minority groups. Despite the achievement of greater civil rights, BIPOC have continued to have significantly worse outcomes across many health indicators.

Increasing Patient Trust and Involvement

The past several years have seen increased attention to reestablishing patients’ trust in the healthcare system, including particular attention to partnering with people and communities of color. Proposed solutions include increasing the quality of personal interactions; expanding diversity in the workforce; enhancing the respect with which patients are treated; respecting cultural contexts; and aligning incentives, including those between patients and systems.

As an example of a patient-informed approach to building trust, in 2018 UnityPoint Health (a regional healthcare system serving Iowa, Illinois, and Wisconsin) opened its first health clinic offering dedicated services for LGBTQ+ communities [20]. Acknowledging limitations in their knowledge, clinic leadership adopted an approach of cultural humility. They reached out to LGBTQ+ community leaders and members to understand challenges, barriers, and what the health system could do to serve the community’s needs.

To ensure they are providing a welcoming and identity-affirming care environment, clinic staff regularly participate in Safe Zone training. They also focus on having consistent routines, such as asking for and providing pronouns, to build trust. In response to positive feedback from the LGBTQ+ community, UnityPoint has since established additional clinics and is examining how to expand LGBTQ+-inclusive training across its network

What can FQHCs do to Improve Health Equity?

Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) can take several steps to address the issues of building trust and improving racial equity in healthcare quality. These include:

- Increasing cultural and linguistic competence: FQHCs can provide training and resources to staff on cultural humility, language interpretation, and how to effectively communicate with patients from diverse backgrounds.

- Addressing implicit bias: FQHCs can create policies and procedures to address implicit bias and discrimination in the workplace and provide training and resources to staff on how to recognize and address their own biases.

- Increasing diversity in the workforce: FQHCs can actively recruit, retain and promote a diverse workforce that reflects the communities they serve, with a focus on hiring and promoting individuals from underrepresented communities, including BIPOC, and LGBTQ+ communities.

- Involving patients and communities in quality improvement efforts: FQHCs can gather feedback from patients and communities of color on their experiences with the health center and use this feedback to improve care and services. This can include using standardized patient experience questionnaires and involving patients in the design and evaluation of quality improvement efforts.

- Community engagement: FQHCs can strengthen their relationships with community-based organizations, and establish regular communication and collaboration with community leaders, groups, and other stakeholders.

- Example: To help reach Black communities in underserved areas, the LCFA is enlisting the help of a trusted local resource: the hair salon. Hair salons have historically been one of the most accessible local businesses in underserved Black communities. Salons are often seen not only as successful sources of entrepreneurship but as gathering places and community forums. Hairstylists are friends and confidants of their clientele, and are so trusted with personal information they often feel like “Hairapists.”

- LCFA has developed a strategy to leverage the influence of hair salons to distribute valuable and potentially lifesaving information about lung cancer screening. The new initiative features a training video aimed at hairdressers that guides them in explaining the importance of screening, because people of color remain at an increased risk of developing and dying from lung cancer.

- Financial incentives: FQHCs can use financial incentives to achieve equity in healthcare quality, such as rewarding staff for reducing disparities and incentivizing clinicians to provide high-quality, culturally responsive care.

- Improved measurement strategies: FQHCs can use improved measurement strategies to assess outcomes, such as implementing data collection and analysis tools that capture elements of bias and discrimination and reporting on outcomes by race, ethnicity, and other dimensions, and using this information to make improvements.

Share this article and save a life!

Author:

Jonathan is a seasoned executive with a proven track record in founding and scaling digital health and technology companies. He co-founded Oatmeal Health, a tech-enabled Cancer Screening as a Service for Underrepresented patients of FQHCs and health plans, starting with lung cancer. With a strong background in engineering, partnerships, and product development, Jonathan is recognized as a leader in the industry.

Govette has dedicated his professional life to enhancing the well-being of marginalized populations. To achieve this, he has established frameworks for initiatives aimed at promoting health equity among underprivileged communities.

REVOLUTIONIZING CANCER CARE

A Step-by-Step FQHC Guide to Lung Cancer Screening

The 7-page (Free) checklist to create and launch a lung cancer screening program can save your patients’ lives – proven to increase lung cancer screening rates above the ~5 percent national average.

– WHERE SHOULD I SEND YOUR FREE GUIDE? –